By Nicolas Cachanosky, American Institute For Economic Research

The Federal Reserve recently disclosed its preliminary income and expenses for 2023, revealing an unprecedented $114.3 billion in operational losses. Somewhat surprisingly, Fed officials seem unconcerned about this financial performance. Their lack of concern may be even more worrisome than the losses themselves. Like any financial institution, the Fed receives revenue from the financial assets it holds and it must pay interest on its financial liabilities. Arguably, the last round of QE played a role in setting up current Fed losses.

One key aspect of the Federal Reserve Act is its obligation to remit its profits to the US Treasury. When the Fed experiences losses, however, it doesn’t lead to the Treasury cutting a check. Instead, the Fed issues an IOU known as “deferred assets,” essentially monetizing its own deficits. Moving forward, the Fed will use future profits to offset these deferred assets before resuming regular remittances to the Treasury.

The Federal Reserve, in response to these record losses, asserts that a “deferred asset has no implications for the Federal Reserve’s conduct of monetary policy or its ability to meet its financial obligations.” The first statement, that deferred assets have no implications on the execution of monetary policy, is questionable. The second statement, that it has no bearing on the Fed meeting its financial obligations, is redundant.

Firstly, the impact on market expectations is paramount for the effectiveness of monetary policy. Sustained Federal Reserve deficits leading to deferred assets could sow seeds of doubt among the public regarding the Fed’s future actions. While doubts may not come from the Fed itself, they could come from Congress, which may push for the Fed to return to financial stability and resume contributions to the Treasury. Such doubts would have a precedent in the Fed’s increasing involvement in fiscal policy since 2008. The Fed’s recent history jeopardizes the perception that it is independent, which is a crucial element for the effectiveness of monetary policy.

Secondly, claiming that deferred assets have no implications for the Fed’s ability to meet financial obligations acknowledges the Fed’s power to essentially “print” any necessary amount of US dollars it deems fit. While not a groundbreaking revelation for any central bank, the lack of concern about the economic and institutional implications of monetizing financial obligations is cause for concern. The Fed, in its quest to address its deficits, is not only indirectly imposing an inflation tax through fiscal policy but is also normalizing a potentially hazardous misapplication of its authority to issue currency. This is a very slippery slope that typically does not end well. The fact that the Treasury does not cut a check to the Fed to cover its losses does not mean the Fed’s losses are a free lunch. There is, after all, no such thing. The Fed’s losses are paid by the implied inflation that originated in the Fed monetizing its own deficits.

The Federal Reserve finds itself in new territory, grappling with substantial deficits for the first time in its history. It is essential to question whether the Fed’s nonchalant attitude toward its record losses truly reflects a prudent strategy — or, if it is a precarious stance on a slippery and potentially perilous path.

From FederalReserve.gov:

The Federal Reserve Board on Friday released preliminary financial information for the Federal Reserve Banks' income and expenses in 2023. The 2023 audited Reserve Bank financial statements are expected to be published in coming months and may include adjustments to these preliminary unaudited results.

Information related to the 2023 preliminary financial results for the Reserve Banks include:

The Reserve Banks' 2023 sum total of expenses exceeded estimated earnings by $114.3 billion. In 2022, net income was $58.8 billion;

Interest income on securities acquired through open market operations totaled $163.8 billion in 2023, a decrease of $6.2 billion from 2022 interest income of $170.0 billion;

Total interest expense of $281.1 billion increased $178.7 billion from 2022 total interest expense of $102.4 billion; of the increase in interest expense, $116.3 billion pertained to interest expense on reserve balances held by depository institutions and $62.4 billion related to interest expense on securities sold under agreements to repurchase;

Total interest income earned on loans to depository institutions and other eligible borrowers, including from the Bank Term Funding Program and Paycheck Protection Program Liquidity Facility, was $10.4 billion;

Operating expenses of the Reserve Banks, net of amounts reimbursed by the U.S. Treasury and other entities for services the Reserve Banks provided as fiscal agents, totaled $5.5 billion in 2023;

In addition, the Reserve Banks were assessed $1.0 billion for the costs related to producing, issuing, and retiring currency; $1.1 billion for Board expenditures; and $0.7 billion to fund the operations of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau.

The Reserve Banks realized net income of $0.1 billion from emergency credit facilities established in response to the COVID-19 pandemic;

Additional earnings were derived from income from payment and settlement services of $0.5 billion;

Statutory dividends totaled $1.5 billion in 2023.

The Federal Reserve Act requires the Reserve Banks to remit excess earnings to the U.S. Treasury after providing for operating costs, payments of dividends, and an amount necessary to maintain surplus.

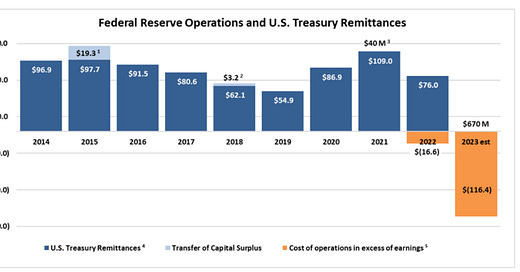

During a period when earnings are not sufficient to provide for those costs, a deferred asset is recorded. In 2023, the Reserve Banks increased the deferred asset by $116.4 billion resulting in a cumulative deferred asset at year-end of $133.0 billion. The deferred asset is the amount of net excess earnings these Reserve Banks will need to realize before their remittances to the U.S. Treasury resume. A deferred asset has no implications for the Federal Reserve's conduct of monetary policy or its ability to meet its financial obligations. The attached chart illustrates the amount the Reserve Banks distributed to the U.S. Treasury from 2014 through 2023 (estimated).

About the Author

Dr. Cachanosky is Associate Professor of Economics and Director of the Center for Free Enterprise at The University of Texas at El Paso Woody L. Hunt College of Business. He is also Fellow of the UCEMA Friedman-Hayek Center for the Study of a Free Society. He served as President of the Association of Private Enterprise Education (APEE, 2021-2022) and in the Board of Directors at the Mont Pelerin Society (MPS, 2018-2022).

He earned a Licentiate in Economics from the Pontificia Universidad Católica Argentina, a M.A. in Economics and Political Sciences from the Escuela Superior de Economía y Administración de Empresas (ESEADE), and his Ph.D. in Economics from Suffolk University, Boston, MA.

QTR’s Disclaimer: I am an idiot and often get things wrong and lose money. I may own or transact in any names mentioned in this piece at any time without warning. Contributor posts and aggregated posts have not been fact checked and are the opinions of their authors and are either published with the author’s permission or under a Creative Commons license. This is not a recommendation to buy or sell any stocks or securities, just my opinions. I often lose money on positions I trade/invest in. I may add any name mentioned in this article and sell any name mentioned in this piece at any time, without further warning. None of this is a solicitation to buy or sell securities. These positions can change immediately as soon as I publish this, with or without notice. You are on your own. Do not make decisions based on my blog. I exist on the fringe. The publisher does not guarantee the accuracy or completeness of the information provided in this page. These are not the opinions of any of my employers, partners, or associates. I did my best to be honest about my disclosures but can’t guarantee I am right; I write these posts after a couple beers sometimes. Also, I just straight up get shit wrong a lot. I mention it twice because it’s that important.

That is just one reason they need to be audited. There has never been one...

At the very least they ought to cut operating expenses and fire half of their PhD economists, who can’t predict their way out of a paper bag.